PETITION FOR THE LISTING OF THE ATLANTIC WHITE MARLIN

AS A THREATENED OR ENDANGERED SPECIES

The Biodiversity Legal Foundation (BLF) and James R. Chambers hereby petition to list as threatened or endangered the Atlantic white marlin, Tetrapturus albidus Poey (1860), throughout its known range, and to designate critical habitat under the Endangered Species Act, 16 U.S.C. §§ 1531-1544 (ESA). This petition is filed under 5 U.S.C. § 553 (e), 16 U.S.C. § 1533, and 50 C.F.R. §§ 424.14, 424.10 which give interested persons the right to petition for issuance of a rule. The National Marine Fisheries Service (NMFS), within the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), within the Department of Commerce, has jurisdiction over this petition under 16 U.S.C. § 1533 (a) of the ESA.

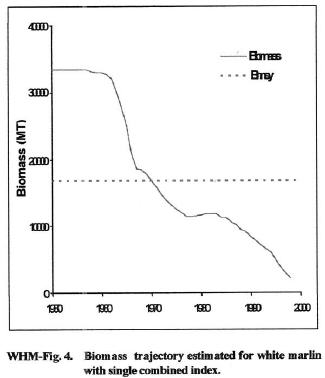

The Atlantic white marlin merits listing as a threatened or endangered species under the ESA because its population has declined to the point that it is now threatened with extinction throughout its range. As discussed in detail in Section VIII, below, the best available scientific information has documented a severe population (or stock) decline caused by commercial over-fishing by many nations (targeting swordfish and tunas). Increasingly severe overfishing has been allowed to exist for over 30 years by the International Commission for the Conservation of Atlantic Tunas (ICCAT), which claims management authority for all Atlantic tunas and tuna-like fishes. The population's decline has been documented thoroughly by ICCAT's scientific advisors, the Standing Committee for Research and Statistics (SCRS). Stock assessments conducted by the SCRS represent the consensus of the world scientific community. According to the SCRS's latest stock assessment conducted in July of 2000 (SCRS/00/23, reproduced in Appendix 1), the population's abundance was last at its long-term sustainable level in 1980. By the end of 1999, its abundance had declined to only 13 percent of its sustainable level. Depicted below is the record of 40 years of decline (source: WHM-Fig.4 , SCRS/00/04B).

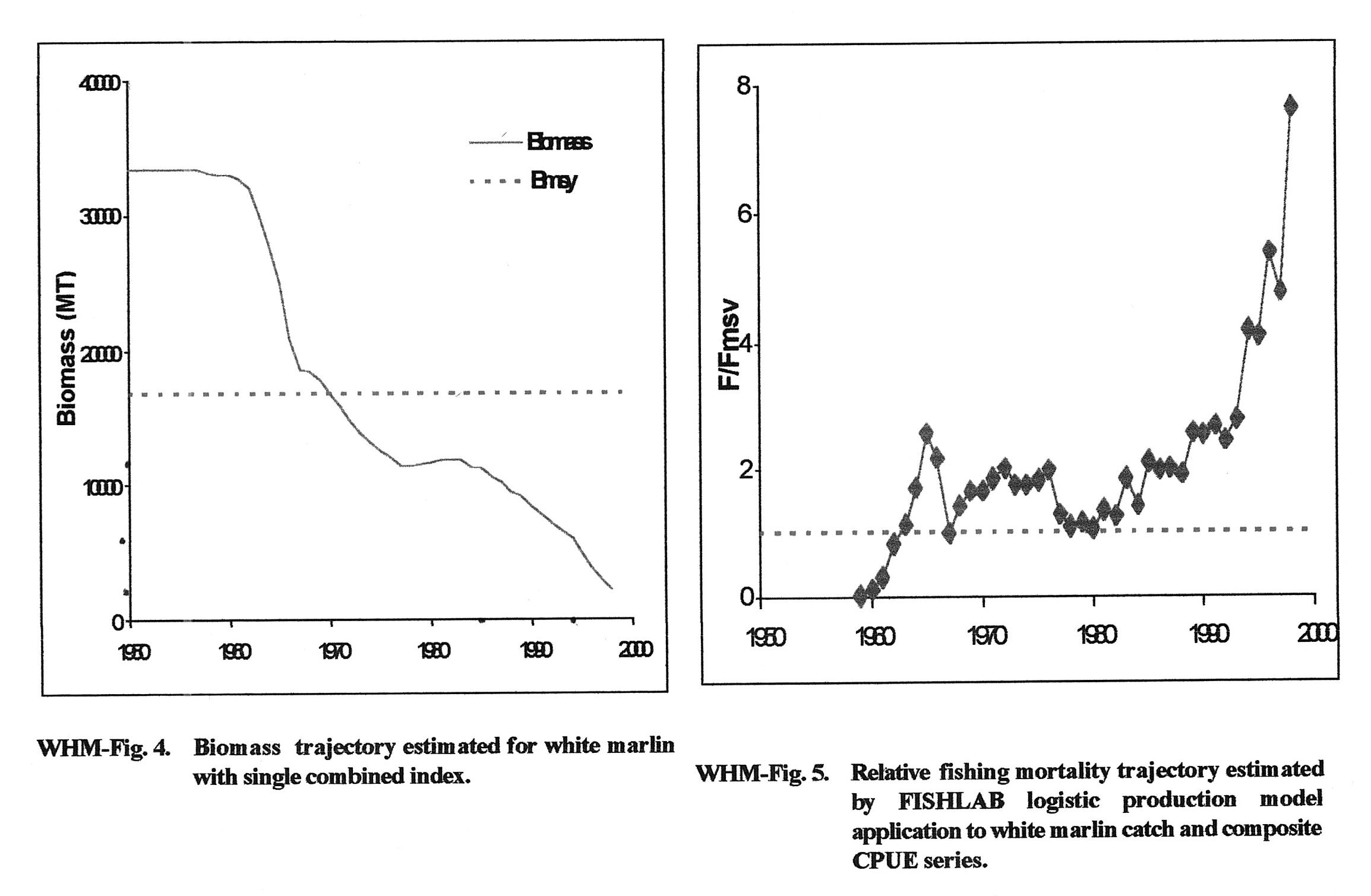

The cause: fishing mortality (fishing pressure) had been allowed to rise dramatically to 8 to 10 times the sustainable level by the end of 1999. At this rate of decline, the species will become functionally or ecologically extinct well within the foreseeable future (in less than five years) unless dramatic remedial action is taken both nationally and internationally, as we recommend herein. Based on the detailed record developed by the SCRS for ICCAT, it is clear that the existing international and domestic regulatory mechanisms and programs controlling fishing have long been inadequate to conserve white marlin. Domestically, this is the responsibility of the Secretary of Commerce acting though NMFS. The domestic and international fishery management bodies have failed to limit catches sufficiently and protect key habitats (i.e., prime spawning and feeding areas) in order to maintain the white marlin population at its long-term sustainable level (ICCAT's stated management objective). Failure to maintain a healthy white marlin population undermines the objectives of the Atlantic Billfish Fishery Management Plan (FMP) (SAFMC, 1988) and fails to comply with the basic requirements of the Magnuson-Stevens Fishery Conservation and Management Act (Magnuson-Stevens Act). The latter stipulates that populations of fishery resources are to be maintained at their optimum yield (an abundance greater than the long-term sustainable level) and bycatch (the incidental capture of unintended, unwanted or prohibited species) is to be avoided and minimized.

I. Petitioners

The Biodiversity Legal Foundation (BLF) is a science-based, non-profit organization dedicated to the preservation of all native wild plants and animals, communities of species, and naturally functioning ecosystems. Through visionary education, administrative, and legal actions, the BLF endeavors to encourage improved public attitudes and policies for all living things. The BLF has tracked changes in the biological status of numerous imperiled marine and estuarine species over the past 10 years.

James R. Chambers is a fisheries biologist with 36 years of professional experience. He is the principal of Chambers and Associates, a scientific consultancy specializing in conserving marine fish and their essential habitats. For the final two years of his 30-year federal government career, he was responsible for management of Atlantic swordfish and billfish in the Highly Migratory Species Management Division in NMFS headquarters. He holds a M.A. degree in Marine Science from the Virginia Institute of Marine Science, College of William and Mary.

II. Statutory Framework: the Endangered Species Act and the Administrative Procedure Act

This section of the petition briefly reviews the purposes of the ESA, the listing and critical habitat designation process, substantive protections provided by the ESA, and the provision of the Administrative Procedure Act (APA) that allows people to petition for the issuance of a rule.

A. Purposes of the Endangered Species Act

While the Endangered Species Preservation Act of 1966, Pub. L. No. 86-699, 80 Stat. 926, and the Endangered Species Conservation Act of 1969, Pub. L. No. 91-135, 83 Stat. 275, laid the framework for federal efforts to conserve endangered species, Congress recognized in 1973 that existing law "simply d[id] not provide the kind of management tools needed to act early enough to save a vanishing species." S. Rep. No. 307, 93rd Cong., 1st Sess. 3 (1973). Accordingly, in enacting the ESA, Congress intended to "widen the protection which can be provided to endangered species." H. R. Rep. No. 412, 93rd Cong., 1st Sess. 1 (1973). "As it was finally passed, the Endangered Species Act of 1973 represented the most comprehensive legislation for the preservation of endangered species ever enacted by any nation." Tennessee Valley Authority v. Hill, 437 U.S. 153, 180 (1978).

Congress understood that "[t]hroughout the history of the world, as we know it, species of animals and plants have appeared, changed, and disappeared," but at the same time, Congress believed that the disappearance of species appeared to be accelerating. H. R. Rep. No. 412, 93rd Cong., 1st Sess. 4 (1973). As the Committee on Merchant Marine and Fisheries noted, this belief provided "an occasion for caution, for self-searching and for understanding. Man’s presence on the Earth is relatively recent, and his effective dominion over the world’s life support systems has taken place within a few short generations. Our ability to destroy, or almost destroy, all intelligent life on the planet became apparent only in this generation. A certain humility, and a sense of urgency, seem indicated." Id.

In light of this concern, Congress intended that the ESA "provide a means whereby the ecosystems upon which endangered species and threatened species depend may be conserved, [and] to provide a program for the conservation of such endangered species and threatened species…." 16 U.S.C. § 1531(b). In turn, conserve was expansively defined as the "use of all methods and procedures which are necessary to bring any endangered species or threatened species to the point at which the measures provided pursuant to [the ESA] are no longer necessary." Id.

"The listing process under Section 4 is the keystone of the Endangered Species Act… The proper operation of this section is critical to the implementation of the Act, as it determines which species receive the protections of the Act." H. R. Rep. No. 567, 1982 U.S.C.C.A.N. 2810, 2819.

Several sections of the regulations implementing the ESA (50 C.F.R.) are applicable to this petition. Those concerning the listing of the Atlantic white marlin as a threatened or endangered species are:

424.02(e) Endangered species means a species that is in danger of extinction throughout all or a significant portion of its range. (m) Threatened species means any species that is likely to become an endangered species within the foreseeable future throughout all or a significant portion of its range. (k) Species includes any species or subspecies…and any distinct population segment of any vertebrate species that interbreeds when mature.

424.11(c) "A species shall be listed . . . because of any one or a combination of the following factors:

Four of the factors set out in section 424.11(c) are applicable to the Atlantic white marlin: overutilization for commercial purposes, predation, inadequacy of existing regulatory mechanisms and other natural or manmade factors affecting its continued existence. These are discussed in detail in Section IX, below.

Based on the documentation provided below, petitioners contend that the provisions of 50 C.F.R. compel the expeditious listing of the Atlantic white marlin as threatened or endangered throughout its known historic range.

To the maximum extent practicable, within 90 days after receiving the petition of an interested person to add a species to the lists of endangered and threatened species, the Secretary shall make a finding as to whether the petition presents substantial scientific or commercial information indicating that the petitioned action may be warranted. 16 U.S.C. § 1533 (b)(3)(A). If the petition is found to present such information, the Secretary shall promptly commence a review of the status of the species. Id.

Within 12 months after receiving a petition that is found under section 4(b)(3)(A) to present substantial information indicating that the petitioned action is warranted, the Secretary shall make one of three findings: that the petitioned action is not warranted, that the petitioned action is warranted, in which case the Secretary publishes the proposed regulation in the Federal Register, or that the petitioned action is warranted but precluded. 16 U.S.C. §1533(b)(3)(B).

Within the one-year period beginning on the date the general notice is published regarding a proposed regulation, the Secretary shall publish in the Federal Register, if a determination as to whether a species is endangered or threatened, or a revision of critical habitat, is involved, either a final regulation to implement the determination, a final regulation to such revision or a finding that such revision should not be made, notice that the one-year period is being extended, or notice that the proposed regulation is being withdrawn. Id. at § 1533 (b)(6)(A). If the Secretary finds with respect to a proposed regulation that there is a substantial disagreement regarding the sufficiency or accuracy of the available data relevant to the determination or revision concerned, the Secretary may extend the one-year period for not more than six months for the purposes of soliciting additional data. Id. at § 1533 (b)(6)(B)(i).

A final regulation designating critical habitat of an endangered species or a threatened species shall be published concurrently with the final regulation implementing the determination that such species is endangered or threatened, unless the Secretary deems that it is essential to the conservation of such species that the regulation implementing such determination be promptly published, or critical habitat of such species is not determinable, in which case the Secretary, with respect to the proposed regulation to designate such habitat, may extend the one-year period by not more than one additional year, but not later than the close of such additional year the Secretary must publish a final regulation, based on such data as may be available at that time, designating, to the maximum extent prudent, such habitat. 16. U.S.C. § 1533 (b)(6)(C).

By statute, critical habitat is defined as:

Id. at § 1532(5). The determination of critical habitat shall be based on the best scientific data available. 50 C.F.R. § 412.12.

The Secretary, in designating critical habitat, shall identify any significant activities that would either affect an area considered for designation as critical habitat or be likely to be affected by the designation, and shall, after proposing designation of such an area, consider the probable economic and other impacts of the designation upon proposed or ongoing activities. 50 C.F.R. § 424.19. The Secretary may exclude any portion of such an area from the critical habitat "if the benefits of such exclusion outweigh the benefits of specifying the area as part of critical habitat." Id. However, the Secretary "shall not exclude any such area if, based on the best scientific and commercial information available, he determines that the failure to designate that area will result in the extinction of the species concerned." Id.

Regulations implementing section 4 provide additional procedural considerations. Critical habitat shall be specified to the maximum extent prudent and determinable at the time a species is proposed for listing. 50 C.F.R. § 412.12. A designation of critical habitat is not prudent when one or both of the following situations exist: the species is threatened by taking or other human activity, and identification of critical habitat can be expected to increase the degree of threat to such species, or the designation of critical habitat would not be beneficial to the species. Id. at § 412.12(a)(1). Critical habitat is not determinable when one or both of the following situations exist: information sufficient to perform required analyses of the impacts of the designation is lacking, or the biological needs of the species are not sufficiently well known to permit identification of an area as critical habitat. Id. at § 412.12(a)(2).

In determining what areas are critical habitat, the Secretary "shall consider those physical and biological features that are essential to the conservation of a given species and that may require special management considerations or protection." 50 C.F.R. § 412.12(b). Such requirements include, but are not limited to: space for individual and population growth, and for normal behavior; food, water, air, light, minerals, or other nutritional or physiological requirements; cover or shelter; sites for breeding, reproduction, rearing of offspring, germination, or seed dispersal; and habitats that are protected from disturbance or are representative of the historic geographical and ecological distributions of a species. Id.

When considering the designation of critical habitat, the Secretary shall focus on the principal biological or physical constituent elements within the defined area that are essential to the conservation of the species. Id. Known constituent elements shall be listed with the critical habitat description. Id. Primary constituent elements may include, but are not limited to, roost sites, nesting grounds, spawning sites, feeding sites, seasonal wetland or dry land, water quality or quantity, host species or plant pollinator, geological formation, vegetation type, tide, and specific soil types. Id.

Once a species is listed, the ESA contains several different substantive protections for listed species. Section 4(f) of the ESA requires that the Secretary prepare a Recovery Plan for the species, unless he finds that such a plan will not promote the conservation of the species. 16 U.S.C. § 1533(f). In developing and implementing such a plan, the Secretary shall, to the maximum extent practicable, incorporate in each plan "a description of such site-specific management actions as may be necessary to achieve the plan’s goal for the conservation and survival of the species." 16 U.S.C. § 1533(f)(1)(B)(i).

Under Section 7 of the ESA, each federal agency "shall… insure that any action authorized, funded, or carried out by such agency … is not likely to jeopardize the continued existence of any endangered species or threatened species or result in the destruction or adverse modification of habitat of such species which is determined by the Secretary… to be critical…." Id. at § 1536(a)(2). "Destruction or adverse modification" is defined by a regulation as "a direct or indirect alteration that appreciably diminishes the value of critical habitat for both the survival and recovery of a listed species. Such alterations include, but are not limited to, alterations adversely modifying any of those physical or biological features that were the basis for determining the habitat to be critical." 50 C.F.R. § 402.02.

D. Administrative Procedure Act

The APA requires each federal agency to "give an interested person the right to petition for the issuance, amendment, or repeal of a rule." 5 U.S.C. 553(e).

III. Legal Status of Atlantic White Marlin

Existing legal protection for Atlantic white marlin at both the national and international level is inadequate to conserve the species or prevent its slide toward extinction. Following is a discussion of its limited protection at each level.

ICCAT, which claims management authority over tunas and tuna-like fishes of the Atlantic Ocean, considers the Atlantic white marlin stock (or population) to be overfished and that

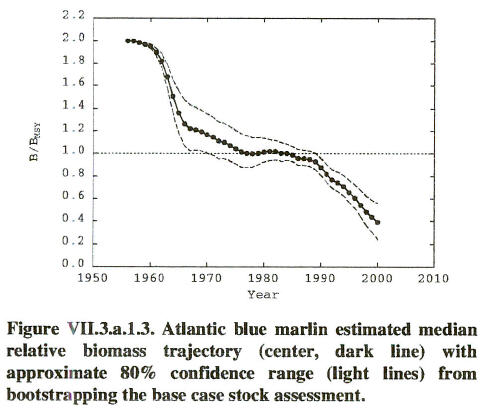

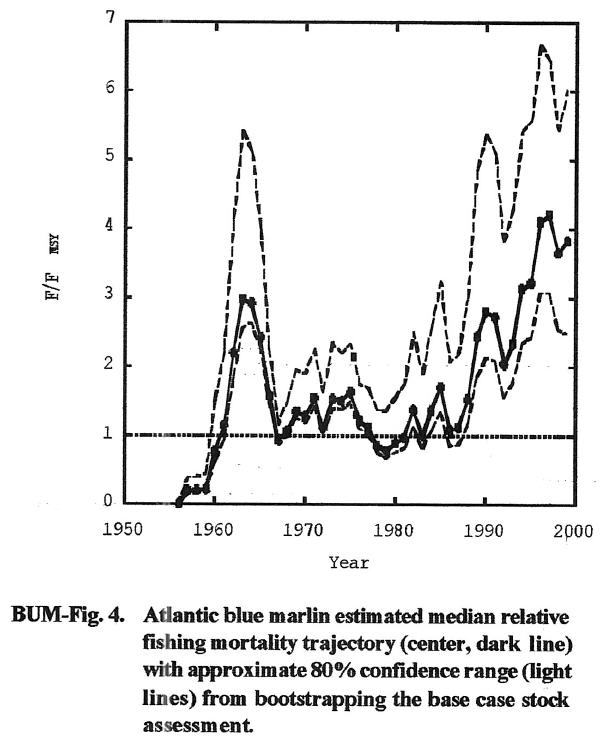

overfishing has taken place for over three decades (SCRS/00/23, SCRS/00/04B). These terms and other technical aspects of fishery stock assessment are discussed in detail in Section VIII., below. ICCAT is described in more detail in Section V.B.2., below. The disturbing results of the latest Atlantic marlin stock assessment (conducted in 2000) are reproduced in Appendix 1 (SCRS Fourth Billfish Workshop Report, SCRS/00/23) and summarized in the Executive Summaries for White Marlin (SCRS/00/04B) and Blue Marlin (SCRS/00/03B), both reproduced in Appendix 2. In view the severity of the population declines of Atlantic white marlin (see Appendix 2, WHM-Fig. 4) and Atlantic blue marlin (see BUM-Fig. 3), ICCAT has adopted what are to be considered binding recommendations calling for additional landings reductions by its members to reduce the excessive and still escalating level of fishing mortality for both stocks (see WHM-Fig. 5 and BUM-Fig. 4). Specifically, it has recommended that, beginning June 1, 2001, all of its 31 member nations reduce their white marlin landings by 67 percent and blue marlin landings by 50 percent from each member's 1999 landings levels, and that all live billfish be released. (However, as discussed below, reduction in reported landings does not mean that white marlin mortality will be reduced sufficiently to keep the species from meriting listing.) Retention of billfish unavoidably killed is permitted provided they are not sold. Several artesianal fisheries with minor landings were exempted from these limits. (Annex 7-13, reproduced in Appendix 4).

2. United States

The Atlantic white marlin is not listed as threatened or endangered under the ESA. However, it was first listed as overfished in 1997 by the Department of Commerce (NMFS, 1997) as required by the Magnuson-Stevens Act (16 U.S.C. § 1801) as amended by the Sustainable Fisheries Act of 1996 (SFA) (Pub. L. 104-297). (The most recent Secretarial listing of overfished species is contained in NMFS, 2001c.) Billfish are reserved solely for the recreational sector (no commercial sale, landings or possession) under the Atlantic Billfish FMP. However, as will be discussed below, most documented billfish mortality (approximately 99 percent) is caused by commercial fishing as bycatch - marine species that are caught unintentionally and often discarded, usually dead or dying. The current minimum recreational size limit is 66 inches lower jaw fork length (LJFL) for white marlin and one marlin (white or blue) landed per vessel per day. At the 2001 ICCAT meeting, the U.S. agreed to limit its recreational billfish landings to 250 marlin per year (a figure somewhat larger than its recent documented landings). ICCAT's new recommendations are to be implemented and self-enforced beginning June 1, 2001.

There are several international conventions and national laws that are important to the management of Atlantic white marlin. They, and the entire U.S. fishery management regime, are discussed in detail in Amendment 1 to the Atlantic Billfish FMP (NMFS, 1999a). These include:

IV. Description of Atlantic White Marlin

The scientific name of the Atlantic white marlin species is Tetrapturus albidus Poey (1860). Common names include white marlin or Atlantic white marlin and locally spikefish or aguja blanco. Other species of the genus Tetrapturus include striped marlin (T. audax), longbill spearfish (T. pfluegeri), shortbill spearfish (T. angustirostris), Mediterrenaen shortbill spearfish (T. belone) and roundscale spearfish (T. georgii). These species are classified within the family, Istiophoridae or billfishes. Others in the billfish family include blue marlin (Makaira nigricans), black marlin (M. indica) and sailfish (Istiophorus platypterus). The Istiophoridae are classified in the suborder Scombroidei, which also includes the swordfish (Xiphias gladius - sole member of the family Xiphiidae) and the tunas (family Scombridae).

The white marlin is a sleek, powerful fish of the open ocean colored deep blue on the upper half of its body and silvery-white on its lower half, armed with a long, sharp-pointed bill (for feeding and defense) and having a long tapered dorsal fin. Like all the Istiophoridae, the bill is formed by the prolongation of the snout and upper jaw, from which the family derives its name. In white marlin, its length (measured from the eye) is about twice the distance from the eye to the posterior edge of the gill cover. Marlin lack teeth except as larvae when their bodies are greatly different with large heads, a shortened trunk and small ovate tails. Their bodies grow to be long, streamlined, and powerful. The caudal fin is large, stiff and lunate (deeply forked). A pair of longitudinal keels on each side of the caudal peduncle increases its strength and thrust. White marlin have a long first dorsal fin which extends from the nape two-thirds the length of the trunk in a typical falcate outline. Its body is colored dark blue on its dorsal surface, pale on the sides and white on its belly. The lateral line is not readily visible, nor are its tiny lanceolate scales. For an illustration see Bigelow and Schroeder (1953).

White marlin grow to at least 9.2 feet. (280 cm) total length (TL) and 181 pounds (82 kg) although few reach a weight of 125 pounds. Females grow larger than the males (Nakamura, 1985, Mather et al., 1975). There are no morphological features or color patterns to differentiate the sexes. White marlin females mature on average at about 45 pounds and a length of 61 inches LJFL while males mature at about 40 pounds and about 55 inches LJFL (de Sylva and Breeder, 1997). White marlin first become vulnerable to commercial fisheries at about 30 pounds (NMFS, 1999a). They may live for 25 to 30 years of age (NMFS, 1999a) producing dramatically larger numbers of eggs with increasing size.

V. Significance

The Istiophoridae (billfishes) are apex or top predators of the open ocean. They are some of the largest and swiftest animals in the sea and display behavioral, anatomical, and physiological adaptations for a mobile open-sea existence. White marlin, at a maximum weight of perhaps 200 pounds, are the smallest of the world's four marlin species. Maximum sizes of the others are perhaps 3,000 pounds for blue marlin, 2,500 pounds for black marlin and 550 pounds for striped marlin. White marlin are slightly smaller than Pacific sailfish and about double the maximum size of Atlantic sailfish and the various spearfish. Swordfish can weigh more than 2,200 pounds. However, they are so different in many other respects from the other billfish, that they are the only species in a completely separate family (Xiphidae). Both black and striped marlin are found only in the Pacific and Indian Oceans, while blue marlin and swordfish are found in all three oceans.

Each Istiophorid species has evolved to fill a specific niche centered on best exploiting the available prey and occupying somewhat different habitats in search of that prey. A pelagic and oceanic species, white marlin usually swim above the thermocline in waters with surface temperatures of more than 22°C. They frequent the higher latitudes of the northern and southern hemispheres only during their respective warm seasons, phased six months apart (as illustrated in WHM-Fig. 1. And BUM-Fig1 reproduced in Appendix 2). Unlike blue marlin, white marlin are found only in the Atlantic Ocean and adjacent seas (SCRS/00/23). They are epipelagic, being found primarily in the upper 300 to 600 ft (100 to 200 m) of open-sea areas, and neritic (utilizing the waters over the continental shelf), and are also found in coastal waters seasonally. White marlin can be found off the American East Coast from Nova Scotia to Brazil, and on the eastern side of the Atlantic Ocean from southern Europe (including the Mediterranean Sea) to South Africa (NMFS, 1999a). While their abundance has declined by more than 90 percent, we are aware of no published studies documenting a collapse in their range. Anecdotal evidence (see statement by Dr. Safina, below) suggests their inshore abundance has diminished with the decline in their abundance. They now appear to be found predominantly in only their essential habitats. Their key spawning and fall feeding areas are located at the extremes of their range, as will be discussed below. Concentrations of white marlin are seen in the summer and the early fall in the Middle Atlantic Bight, the northern Gulf of Mexico, and off La Guaira, Venezuela.

White marlin migrate thousands of miles annually throughout the tropical, subtropical, and temperate waters of the Atlantic Ocean and its adjacent seas. As adults, they feed at the top of the marine food web. Their food resources (small fishes and invertebrates such as squid that can be swallowed whole) are distributed in patches and occur at relatively low densities compared to prey for more generalized (lower trophic level) feeders. The foraging and movement patterns of white marlin and other billfish reflect the distribution and scarcity of appropriate prey in the open seas; these species therefore must cover vast expanses of the ocean in search of sufficient food resources (Helfman et al., 1997). Consequently the distribution of billfish is often correlated with areas with higher densities of prey, such as current boundaries, convergence zones, and upwelling areas. White marlin (like blue marlin and swordfish) are solitary hunters, not schooling species, as are the tunas. However, all these top predators can become concentrated in areas with dense aggregations of prey, which are found in these prime feeding locations.

White marlin are sought as a premiere big game species in the United States, in the Caribbean region and throughout their Atlantic Ocean range (IGFA, 2001). According to the SCRS (Appendix 1), white marlin are also taken commercially by longline, entanglement or gillnet fisheries and by purse seine fisheries which target swordfish and the larger tunas, especially in the western Atlantic. A small number are taken by directed artisanal fisheries using small craft in the Caribbean and along the South American coast. They are also caught incidentally (as bycatch) in tropical tuna longline fisheries that use shallow gear deployment.

The highest reported catches of white marlin by the world's industrial fleets have occurred historically in the western central Atlantic (including the Gulf of Mexico and Caribbean), across the central Atlantic in a broad band on either side of the equator lying between Africa and South America, and in a large area off Brazil extending eastward to well beyond the Mid-Atlantic Ridge and nearly to Africa. Historical catch distributions are portrayed graphically by quarter in WHM-Fig.1 of the Executive Summary for the most recent SCRS stock assessment report (SCRS/00/04B in Appendix 2. The historical white marlin catch by ICCAT member countries is quantified in WHM-Table 1, which has also been reproduced in Appendix 2.

The historical catch of white marlin by the U.S. commercial and recreational sectors is portrayed graphically in Fig. 2.1.14 of Amendment 1 to the Atlantic Billfish FMP (NMFS, 1999a). A dramatic decline in recreational landings is obvious beginning in the late 1980s. This decline was the result of voluntary efforts by this sector to promote conservation of the declining billfish populations. The conservation-oriented decline in blue marlin landings by the recreational sector, as portrayed in Figure 2.1.13, began even earlier. During the same period, bycatch of marlin by the commercial sector actually increased. It did so in proportion to the increasing effort (total hooks fished per year) (NMFS, 1999a).

1. Recreational Fisheries

Many anglers consider marlin as the premiere big game fish, worldwide, and billfish anglers are the elite of the recreational fishing community (Ditton, 2000). From the days of authors Ernest Hemmingway and Zane Grey, and the other pioneers of the sport of big game fishing early in the 20th century, catching a large billfish has been considered by many as the ultimate feat in angling. They are big and fast, fight heroically, and jump spectacularly. Consequently, they are wonderful adversaries to play on relatively light sport fishing tackle, which gives the advantage to the fish. To succeed in conquering a large marlin on sport fishing tackle requires the utmost skill and luck on the part of the angler and crew. To have caught one is generally the ultimate achievement in an angler's life. Accordingly, their existence value to the worldwide angling community is inestimable but enormous. This community and those who simply care about conserving the top predators (the "lions and tigers of the seas") numbers well over one quarter of a million. There are over 230,000 billfish anglers in the United States alone (ASA, 1996); annually, they spend an estimated 2,137,000 days billfishing (Ditton and Stoll, 1998). As will be discussed in detail below, they also spend billions of dollars annually to enjoy the excitement of just seeing and fighting such magnificent fish. U.S. billfish anglers spent an estimated $2.13 billion in 1995 in pursuit of their sport (ASA, 1996). This is many times more, by orders of magnitude, than billfish bring annually when sold commercially, as discussed below. Most anglers consider themselves to be strong advocates for conservation of the Atlantic billfish resources (NMFS, 1999a). Today, virtually all billfishing by sport fishers is "catch-and-release." According to government surveys and estimates by sport fishing organizations, anglers release more than 90 percent of the marlin and sailfish they catch. These statistics are discussed in detail below.

Billfish are pursued for sport at "hot spots" throughout their ranges in the Atlantic, Pacific and the Indian Oceans and adjacent seas. Top Atlantic billfish destinations include the Azores, Madeira, Canary Islands, Bom Bom, Ghana, Brazil's Royal Charlotte Bank, Venezuela's La Guaira Bank, the Puerto Rico Trench, the North Drop off the Virgin Islands, the Bahamas, Bermuda, the DeSoto Canyon, Cape Hatteras, and the canyons of the U.S. mid-Atlantic. The all-tackle world record white marlin weighed 181 pounds. Like several other line-class world record white and blue marlin, it was caught off Vitoria, Brazil - a probable prime southern hemisphere spawning ground for both blue and white marlin - at the end of the southern hemisphere's spring spawning season (in early December of 1979).

The white marlin is the primary billfish caught from Cape Hatteras, north. They are caught in the greatest number off the U.S. mid-Atlantic coast and are thus a mainstay of this important billfish fishery (Mather, et al., 1975). The sailfish is the prime species caught off both coasts of Florida, and all three species (white marlin, blue marlin and sailfish) are important seasonally throughout the Gulf coast, particularly above submarine canyons (e.g., De Soto) and deep drop-offs of the continental shelf. The rare spearfish are encountered infrequently.

The world’s largest sport fishery for the white marlin occurs in the summer from Cape Hatteras, NC, to Cape Cod, MA, especially between Oregon Inlet, NC, and Atlantic City, NJ. Successful fishing occurs up to 80 miles offshore over submarine canyons and the edge of the continental shelf, extending from Norfolk Canyon in the mid-Atlantic to Block Canyon off eastern Long Island (Mather, et al., 1975). Concentrations are associated with rip currents and weed lines (fronts), and with bottom features such as steep drop-offs, submarine canyons and shoals (Nakamura, 1985). The spring peak season for white marlin sport fishing occurs in the Straits of Florida, southeast Florida, the Bahamas, and off the north coasts of Puerto Rico and the Virgin Islands. (As discussed below, we believe these are their primary spawning grounds.) In the Gulf of Mexico, (post-spawning) summer concentrations are found off the Mississippi River Delta, at De Soto Canyon and at the edge of the continental shelf off Port Aransas, TX, with a peak off the Delta in July, and in the vicinity of De Soto Canyon in August. In the Gulf of Mexico adults appear to be associated with blue waters of low productivity, being found with less frequency in more productive green waters. While this is also true of the blue marlin, there appears to be a contrast in the factors controlling blue and white marlin abundances, as higher numbers of blue marlin are caught when catches of white marlin are low and vice versa (Nakamura, 1985; Rivas, 1975).

Worldwide, billfishing is increasing in popularity. This has stimulated a huge demand for bigger and better vessels (sportfishers), the largest selling for several millions of dollars, the most sophisticated electronics available (computers for viewing charts and real-time navigating, sea surface temperature charts downloaded from satellites, sonar, radar, and communication equipment) and all manner of very expensive fishing tackle. Costs to purchase and equip a boat for offshore fishing probably averages about $300,000 and ranges from about $100,000 to several million dollars for the long-range sportfishers that travel (or are carried or towed by their mothership) around the globe with the seasons to various "hot" destinations. Operating and maintenance costs for the average sportfisher runs about $150,000 per season. The larger vessels have full-time captains and a crew whose salaries add $150,000 to $300,00. The range in annual operating and maintenance costs are even larger (depending on size of vessel).

The popularity of recreational fishing has stimulated an enormous demand for boats, engines, electronic equipment, and a large variety of (very expensive) fishing tackle. According to the IGFA (2001), 79 percent of new boat purchasers plan to fish. In 1999, there were 35 million fishing trips in the U.S. Atlantic. Most (23 percent) were to Florida's east coast. The next most popular (14 percent) was New Jersey's coast (IGFA, 2001). According to Patrick Healey, Executive Vice President of the Viking Yacht Co., speaking for the Marine Manufacturers Association (as reported at www.marlininternational.com/conserva.htm), the recreational boating and fishing industries put $60 billion annually into the U.S. economy. However, he goes on to say, this is "being squandered by the commercial fishing industry….No fish, no fishing boats….The future of the industry looks pretty bleak."

Many serious anglers also fly with their own specialized equipment to the "hot" destinations around the world and charter top captains and their sportfishers for a week or much longer. Such adventures are frequently described in feature articles published monthly in the world's top big game fishing magazines (Marlin, Sport Fishing, the Big Game Fishing Journal, and Salt Water Sportsman) all of which are read internationally. World records for game fish (marine and freshwater species) are awarded and the extensive list is published annually by the International Game Fish Association (IGFA, 2000). IGFA has representatives in many countries worldwide.

Two decades ago, most billfish were brought to the dock to be "hung" and weighed as well as photographed and admired by crowds. The publicity value to charter captains and marina operators was substantial. Now, in an effort to help the dwindling stocks recover, a very high percentage of the fish caught by all U.S. recreational fishermen (including tournaments) are revived and voluntarily released usually with a tag. In 1995, tournament anglers from many nations reported releasing over 92 percent of the billfish they had caught (NMFS, 1997f). The release ethic has spread since then and tournament billfish anglers now report releasing 99 percent of their billfish catches (Ditton, 2000).

The conservation ethic is also spreading. Many traveling anglers will not book a trip with charter crews that do not practice catch and release. And sportfishing fleets at destinations that still have yet to see the benefits of fully adopting this ethic (e.g., Cabo San Lucas Mexico, Hawaii and the Cayman Islands), are shunned by many traveling anglers. Many tournaments are now even adopting a total-release format, which is a significant commitment since it requires independent observers on board each boat. Points are awarded not on the basis of total weight of dead billfish, but on number of releases by species. The major game fishing magazines rarely if ever run pictures of hanging billfish, preferring photos whenever possible that show living fish about to be released. The growing adoption recently of circle hooks (which can penetrate only in the corner of the fish' mouth and thus avoid potentially lethal "gut hooks" or damage to the throat or gills that can be caused by swallowing a bait containing a traditional J-hook) is an additional indicator of the strong conservation ethic that exists throughout the billfish community, worldwide. As noted above, most billfish anglers consider themselves as strong advocates for conservation and they practice conservation in their own fishing. In many areas of the world, there is now a high level of peer pressure throughout the billfishing community against landing any billfish, and killing a white marlin is rare.

Short-term survival of recreationally-caught Atlantic blue marlin (revived as typically practiced by big game fishing community) has been studied recently and, in this limited case, was found to be 88 percent (Graves et al., in press). Of eight blue marlin (150 to 425 lbs.) caught off Bermuda and monitored using pop-off satellite tags, all appeared normal for the five days monitored. The ninth fish was injured during the fight and not expected to live, but tagged to see if it could recover. There have been no post-release survival studies of white marlin caught recreationally (or commercially). However, their survival should be at least as high as that observed in the much larger and stronger blue marlin, particularly as circle hooks replace J-hooks and eliminate the chance for internal injury. According to Hinman (2001), who surveyed fishery scientists that conducted the few billfish catch-and-release studies done to date, "The consensus is that the post-release mortality is probably in the neighborhood of 10 to 15 percent." Hinman also reported results of other tagging studies done: "six blue marlin tracked with no mortalities; 11 striped marlin tracked with all surviving; one mortality among eight sailfish tracked; 23 blue marlin tracked in several different studies, with three deaths."

A controversial study was conducted in the fall of 2000 by the Pfleger Institute of Environmental Research that indicated much higher than normal post-release mortality (Domeier, in press). It was based on 122 striped marlin tagged and released by anglers in Magdalena Bay, Baja, California. Of 40 fish played normally (using 30-pound tackle with similar drag settings), revived and tagged with pop-off satellite tags (set to release if the fish died and sank), 13 or 32 percent apparently did not survive. Many of these were bleeding when released; however, a few fish released strong and healthy also apparently died. The study (especially the methods/equipment employed) has yet to be subjected to full peer review (beginning with its presentation at the World Billfish Symposium in Cairns, Australia, as this document is being prepared). So, its results must be considered only preliminary. Indications from the symposium are that the author may have now changed some pivotal assumptions that radically change the final results thus bringing them more in line with previous studies' findings.

However, a relatively high mortality figure may prove to be an accurate portrayal of the short-term mortality to marlin caught by using live bait with traditional J-hooks as is commonly practiced in some areas, particularly along the Pacific coast of Mexico and in South Florida's "sailfish alley." A long "drop back" is employed to give the billfish ample time to turn the bait in its mouth and to swallow it. If it is swallowed deeply (as is likely), the hook can lodge (initially) in the stomach or throat where it can do great damage to these tissues and to the heart. It can also tear loose (repeatedly) and lodge farther up the throat causing serious injury and producing short fights. Rapid mortality may also result. In contrast, circle hooks can lodge only in the corner of the mouth (the hinge) producing no chance for serious injury. Hook-up percentages are at least comparable. Circle hooks should be used for all fishing (recreational and commercial) where the bait is likely to be swallowed deeply by billfish. J-hooks are appropriate when trolling with dead bait or lures, in which there is no "drop back" or deep swallowing. The clear message should be that to avoid serious injury to the fish you are going to release, use only circle hooks if fishing with live baits. This is a good example of how the recreational and commercial fishing communities can further reduce their billfish mortality. NMFS and the industries themselves should promote and encourage such changes, as the recreational fishing community is now doing. We are confident that as more studies are conducted in the future, we will see that circle hooks eliminate most serious injury and (by also avoiding prolonged fight times by proper tackle selection) can promote high (90 percent or better) post-release survival rates.

Post-release survivorship in tagged bluefin tuna (a similar, more powerful large pelagic species) has also been examined. It was found to be excellent with 97 percent survival for 2 to 30-day deployments of "pop-up" satellite tags on 20 giant bluefin that were caught by anglers (using circle hooks), brought on board for tag implant surgery and subsequently released (Block, et al. 2001). However, in addition to being another example of the advantages of using circle hooks, this high survival rate may also be a reflection of the fact that bluefin are just more hardy than are marlin.

We made an effort to estimated the post-release mortality that might be caused by the 230,000 U.S. billfish anglers (ASA, 1996). Assuming an average rate of 0.25 billfish caught per day of fishing, a total of 2,137,000 days spent fishing per year (Ditton and Stoll, 1998), and a (high) post-release mortality rate of 15 percent (Hinman, 2001), yields a total post-release mortality of just over 80,000 billfish per year, worldwide. Of course, this includes not only the white marlin of the Atlantic but also the blue marlin, sailfish and spearfishes of the Atlantic Ocean and the blue marlin, striped marlin, black marlin, sailfish and spearfishes of the Pacific and Indian Oceans. A little more than half the effort is probably devoted to the Atlantic (we assumed 60 percent or 140,000 anglers) and within it, white marlin represent about 19 percent of the billfish catches (from tournament catch percentages in Table 2.1.8, NMFS, 1999a) for a total potential post-release mortality of roughly 9,000 white marlin per year. This is a significant amount. It represents about 7 white marlin killed per 100 anglers per year from the large Atlantic recreational billfishing sector. The total number potentially killed (9,000) is compared, below, to estimates of post-release mortality that might be produced by U.S. longline vessels.

Under the U.S. Atlantic Billfish FMP (SAFMC, 1988), marlin, sailfish and spearfish are reserved solely for the recreational fishing sector. The total available Atlantic billfish resource, including all white marlin, is thus dedicated by U.S. law entirely to the recreational fishing sector. The recreational rod-and-reel fishery is subjected to minimum size and trip limits (63 Fed. Reg. 14030, March 24, 1998; 63 Fed. Reg. 51859, September 29, 1998). This fishery and its management are described in detail in Amendment 1 (NMFS, 1999a).

2. Commercial Fisheries

As is so with blue marlin, most white marlin landings are incidental to swordfish and tuna longline fisheries (Prince et al., 1991). Marlin, sailfish and spearfish are caught incidentally by all nations whose commercial vessels are targeting swordfish and the larger tunas. The location of the primary commercial fisheries and the gear used is depicted in Fig. 1 of the SCRS Executive Summaries for both white and blue marlin (Appendix 2). The vessels used generally range from large (80+ ft. in length) to very large (300 ft. or more). They are using three primary gear types - drift or pelagic longlines, drift entanglement nets or gillnets and purse seines, as described below.

Longlines, as much as 80 miles in length with up to 1,000 baited hooks, are used by the fleets from more than 31 nations throughout much of the species' range. When set out in parallel, such drift longlines are the equivalent of "underwater minefields" catching everything with a mouth large enough to swallow a 2-inch baited hook or even swim past them and become foul-hooked. U.S. longline vessels range from small (30 ft.), used for short trips like those along the east coast of Florida, to over 100 ft. for the "distant water fleet" fishing during the warmer months on the Grand Banks and beyond to the east (site of the movie, "The Perfect Storm") and during the winter, near the Equator. Such vessels must steam for 10 days from San Juan, Puerto Rico, just to reach these tropical fishing grounds located in the swordfish's primary spawning area (see Appendix 5). The longlines set by smaller vessels are generally 20 to 25 miles in length while those used by the distant water fleet are 40 to 80 miles in length. See Amendment 1 to the Billfish FMP (NMFS, 1999a) for a description of the U.S. longline fleet, its gear and operations. Longlines are responsible for 92.1 percent of the total reported Atlantic white marlin mortality (SCRS/00/23).

Entanglement or drift gillnets are often referred to as "curtains of death." They have large mesh made of clear, nearly invisible monofilament in which many different species of marine life become ensnared and die. Because of their high rate of bycatch (the incidental capture of unintended, unwanted or prohibited species) international agreements now ban the use of such high seas drift nets, which have been as much as 70 miles in length. A "loophole" in the 1992 United Nations agreement still allows their use if less than 2.5 km long.

Purse seines are small mesh nets used to encircle a large mass of fish and then closed or "pursed" by drawing the bottom of the net together. The heavy net is brought on board using a power block and eventually the fish are dipped out of the net as its is reduced to a small pocket. Large, powerful fish such as tuna and marlin injure themselves severely as they crash wildly into each other in the closing space. Purse seines off west Africa, particularly, have often been set around floating objects called "fishery aggregating devices" that attract large numbers of juveniles of many pelagic species. Thus, they too are well known to produce very high bycatch mortalities to non-target but important species, including billfish.

There are also many small-scale coastal subsistence-type fisheries taking marlin. Small boats and handlines are used in the Caribbean (Manooch, 1991) and off Mexico in the Gulf of Mexico and in the Caribbean off Cozumel Island (SCRS/92/77); artisanal fisheries occur off Venezuela and Jamaica (SCRS/00/74, SCRS/92/73), Brazil (SCRS/96/91) and Ghana (SCRS/92/75); and handline and longline fisheries occur off Barbados (SCRS/92/71).

Atlantic blue marlin will be discussed throughout this document because the two species are closely linked by many factors (such as their life history and their catch by commercial vessels), and because the population decline of white marlin is mirrored by that of blue marlin lending additional credence to each population's stock assessment.

Those nations reporting the highest landings of white marlin (in MT) during 1999 from the North Atlantic include: Chinese Taipei (96), Japan (70), EC-Spain (65), Venezuela (42) and Barbados (34). In the South Atlantic, the highest landings were reported by Chinese Taipei (368), Brazil (157) and Japan (22) (SCRS/00/23). Assuming the average white marlin weighs 45 lbs. dressed weight (dw) as calculated below, the total number of white marlin reported caught and killed by the major fishing nations are as follows: in the North Atlantic - Chinese Taipei (4,700), Japan (3,400), EC-Spain (3,200), Venezuela (2,000) and Barbados (1,700). In the South Atlantic - Chinese Taipei (18,000), Brazil (7,700) and Japan (1,000). Landings for the total Atlantic first appeared in the early 1960s, reached a peak of almost 5,000 MT (or about 245,000 white marlin) in 1965 (five years after longlining was introduced), declined to about 1,000 MT (or 49,000 individual fish) per year during the period 1977-1982, and have fluctuated between about 940 and 1,700 MT (or 46,000 to 83,000 white marlin) through 1999 (SCRS/00/23). Landings for the North Atlantic generally show a trend similar to that of the total Atlantic and have followed the intensity of the offshore longline fisheries (SCRS/00/23).

In just 30 years, pelagic longlines have changed the nature of the fishery of swordfish, tunas and billfish - collectively referred to as highly migratory species (HMS). Once a sustainable fishery that focused on large individual fish with little bycatch (NMFS, 1997a), the HMS fishery is now characterized by 50 percent bycatch rates, severely depleted fish populations and shrinking average fish sizes (the average swordfish caught commercially weighs 88 lbs. compared to 300-400 lbs. at the turn of the 20th century (NMFS, 1997a)). By 1999, the total white marlin landings had declined to 908.5 MT - a reduction of 81 percent compared to peak landings in 1965 (SCRS/00/23). This decline has clearly occurred due to the decline in the population's abundance, not because of a change in fishing location or decrease in effort by the commercial fleets. Their effort has in fact increased during this period and the locations fished have not changed significantly (SCRS/00/23). Reported blue marlin catches reached a peak of 4,206 MT in 1990, and by 1999 had declined to 3316 MT - a 21 percent reduction (SCRS/00/23). Again, this decline reflects a smaller blue marlin population rather than a change in fishing locations or reduction in fishing effort, as noted above. The 1999 catch of blue marlin was almost four times that of white marlin (SCRS/00/23). This difference is probably a reflection of their relative population sizes. Both are caught incidentally, and if anything, white marlin are thought to be less selective in their choice of foods, and thus might be more easily caught, than are blue marlin.

According to ICCAT's data, the commercial fishing fleets of the world cause 99.21 percent of the reported annual Atlantic billfish mortality and 99.89 percent of the reported Atlantic white marlin mortality (see Table 1, below). There are currently 31 members of ICCAT. They are listed on ICCAT's website (www.iccat.es). Many other nations' vessels fish illegally side-by-side with ICCAT member nations (e.g., Belize and Honduras, see ICCAT sanction resolution 99-8). They are not members of ICCAT and do not abide by its catch limits. (However, many ICCAT members such as Spain, France and other EU and northern African states also do not always abide by ICCAT's limits.) Neither do they report their catches. All except the U.S. vessels routinely retain and sell billfish (SCRS/00/23) even though they taste oily, are tough and thus have low commercial value as a commodity in comparison to higher value swordfish and the large tunas, which all fleets target. However, marlin flesh is prized in many Asian countries.

Internationally, Atlantic large pelagic fisheries are managed by ICCAT. It has claimed responsibility for the conservation of tunas and tuna-like species in the Atlantic Ocean and adjacent seas. It was established in 1969 at a Conference of Plenipotentiaries, which prepared and adopted the International Convention for the Conservation of Atlantic Tunas that was signed in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, in 1966. About 30 species are of direct concern to ICCAT: Atlantic bluefin, yellowfin (T. albacares), albacore (T. alalunga) and bigeye tuna (T. obesus); swordfish; billfishes such as white marlin, blue marlin, sailfish and spearfish; mackerels such as Spanish mackerel (Scomberomorus maculatus) and king mackerel (Scomberomorus cavalla); and, small tunas like skipjack (Katsuwonus pelamis), black skipjack (Euthynnus alletteratus), frigate tuna (Auxis thazard), and Atlantic bonito (Sarda sarda). According to its website "Through the Convention, it is established that ICCAT is the only fisheries organization that can undertake the range of work required for the study and management of tunas and tuna-like fishes in the Atlantic. Such studies include research on biometry, ecology, and oceanography, with a principal focus on the effects of fishing on stock abundance. The Commission's work requires the collection and analysis of statistical information relative to current conditions and trends of the fishery resources in the Convention area. The Commission also undertakes work in the compilation of data for other fish species that are caught during tuna fishing ("bycatch", principally sharks) in the Convention area, and which are not investigated by another international fishery organization…. The Convention is open for signature, or may be adhered to, by any Government which is a Member of the United Nations or of any specialized agency of the United Nations. Instruments of ratification, approval, or adherence may be deposited with the Director-General of the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO), and membership is effective on the date of such deposit. Currently, there are 31 contracting parties." The delegations from all member countries, except the United States, are dominated entirely by large-scale commercial fishing interests (e.g., dealers, importers, exporters, fleet owners and seafood processing and marketing firms). ICCAT is thus a "thinly veiled" union of commercial fishing interests, as its performance record attests (see Appendix 9).

ICCAT figures indicate that the international recreational fishing community is responsible for less than 1 percent of the reported billfish mortality, Atlantic-wide, as tabulated below.

Table 1. Total Reported Atlantic Billfish Catch and Discards in Relation to the

Catch of the International Sport (Rod and Reel) Fishing Sector in metric tons (MT)

Total Dead Landed by R&R as % of

Caught Discards Rod & Reel Total Caught

Blue Marlin (1999) 3,316 MT 81 MT 44 MT 1.32 %

White Marlin (1999) 908 MT 56 MT 1 MT 0.11 %

Sailfish/Spearfish (1998) 1,730 MT 0 MT 2 MT 0.12 %

Totals 5,954 MT 137 MT 47 MT 0.79 %

Source: ICCAT reports

Blue Marlin and White Marlin - July 2000 Billfish Workshop Report (SCRS/00/23)

Sailfish/Spearfish - Executive Summary, Report of the SCRS on Sailfish-Spearfish (Oct 1999)

For white marlin, international anglers are responsible for only 0.11 percent of the reported Atlantic-wide fishing mortality. Commercial vessels from at least 14 ICCAT member nations are responsible for the remainder - 99.89 percent.

U.S. commercial vessels fishing anywhere in the Atlantic Ocean are prohibited from possessing, retaining, or selling any billfish. The industry refers to these as "regulatory discards." Live billfish must be cut free in a manner intended to promote their survival. U.S. commercial vessels' reported regulatory "dead discards" are listed above. These estimates under-represent the actual mortality, because U.S. longline vessels do not fully report all marlin catches, dead discards or releases, as discussed below. This situation is described at length in the plaintiff's pleading in the pending lawsuit (Civ. No. 1:99-01692, D.C. Cir. 1999) brought by the National Coalition for Marine Conservation against the Secretary of Commerce regarding the agency's failure to minimize billfish bycatch as required by the Magnuson-Stevens Act.

Under-reporting of billfish bycatch by commercial vessels is a problem. Less than five percent of longline trips are monitored by independent observers (2.9 percent in 1998). As public concern has risen over the effects of longlines in decimating populations of billfish, small swordfish and other oceanic species (threatened and endangered sea turtles, marine mammals, etc.) under-reporting may have increased in the past several years, as noted below.

Appendix 6 contains a published interview with a former longline vessel captain describing how U.S. longline vessels routinely under-report the extent of their kill of marlin, sailfish and sub-legal swordfish. It is entitled "Fed-up commercial longliner reveals nightmarish killing on high seas" (Florida Sportsman, 2000). The former longliner points out that they were discouraged by the vessel owner from reporting the bycatch of billfish and other species. "Don't write down nothing. It just adds fuel to the fire." is how it was described. He went on, "I used to fish with a guy who insisted on bringing marlin and sailfish in and cutting their throats; we'd send 'em away bleeding so they wouldn't mess with our gear [get re-hooked]. Hundreds of 'em. It happens all the time. I've done it, and I feel bad about it. That was back [10 years ago] when I first started. I was kind of green. Anything that would mess with the gear, they would kill it."

NMFS has compared the catch reported in mandatory logbooks by U.S. longline vessels with catches on which independent observers were present (Cramer, 1999). To get a more accurate estimate of billfish bycatch than relying solely on commercial vessels' logbook reports, NMFS applied the ratio of observed bycatch to total (logbook) reported effort expended (number of hooks fished) by sampling area and quarter to produce estimates of annual billfish mortality (bykill) (see Cramer, 1996d, 1999; and Cramer and Adams, 1998-2000). Longline vessels were found to consistently under-report the number of small swordfish they discarded (because they were less than 41 lbs. live weight or 33 lbs. dw - the legal minimum size for commercial sale) by a factor of two to four times the number that should have been reported (Cramer, 1999). In other words, the longline vessels caught and discarded two to four times as many baby swordfish as they reported discarding (female swordfish mature at 150 lbs., on average (Arocha, 1999)). According to longliners themselves, over 90 percent of these young fish would have been dead already (Florida Sportsman, 2000; p. 35, NMFS, 1997a). The rest would likely die shortly thereafter as a result of the severe trauma (jaws and gills torn apart) inflicted by the heavy longline gear (p. 15, RFA, 1999). The estimated under-reporting of billfish is much greater than for small swordfish. Longline vessels frequently under-reported the number of white marlin that should have been caught by a factor of 10 to 24 times, blue marlin by a factor of 8 to 26 times, and sailfish by a factor of 9 to 26 times. The higher the catch of billfish, the greater was their under-reporting (Table 1., Cramer, 1999). Clearly, existing legal penalties, observer requirements, and law enforcement are not adequate to ensure accurate reporting of catch and apparently, many do not. However, part of the explanation is due to the fact that billfish are being encountered by observer trips less frequently and thus producing more variability in their estimated catch rate as compared to the more numerous swordfish. We suspect that the actual number of billfish under-reported is probably closer to the swordfish under-reporting rate (i.e., two to four times). Since reporting all fish caught is a legal requirement for all HMS permit holders, there is no valid excuse for any under-reporting.

Using the above approach (based on observer bycatch rates by reporting area times the total number of hooks fished), NMFS estimated that in 1995, the U.S. commercial vessels' bykill was 3,658 white marlin. NMFS also estimated a bykill of 2,190 blue marlin and 2,739 sailfish (Cramer and Adams, 1999). The U.S. fleet size would then have been somewhat less than 300 active vessels directly involving about 1,200 crew members (Section 4.4.2, NMFS, 1997a). We recognize that these types of bycatch estimates are not precise since they are based on interception rates of relatively infrequent events collected during less than five percent of longline vessels' trips that were observed and expanding these interception rates to the entire fleet. However, they are the best scientific and commercial data available and they do show at least order of magnitude trends over time. We believe these estimates for 1995 are reasonably accurate or at least they are relatively consistent with those of previous years. After the mid-1990s, the longliners' reporting appears to have changed. With the rise in public concern over the damage being done, there is evidence (see Table 6.7 of NMFS, 2000a) that the amount of marlin bycatch that was reported by longliners had decreased substantially each year and at a higher rate of decline than the documented decline in the two marlin populations, which will be discussed in detail in Section VIII. Accordingly, we think 1995 may be the last year for which there exist relatively reliable data on billfish catch and bycatch that has been reported by U.S. longline vessels.

In contrast, the available information suggests that the recreational fishing sector, numbering in the hundreds of thousands of participants, causes much more limited direct mortality (due to landings) to the Atlantic white marlin population. In 1999, tournament anglers reported catching 2,683 marlin in 118,488 hours of effort. A total of 177 blue marlin and 36 white marlin were boated (NMFS, 2001a). In 2000, preliminary NMFS data from tournaments indicate that 106 blue marlin and 8 white marlin were landed (Buck Sutter, personal communication, August 23, 2001N). Non-tournament anglers (on charter boats or private vessels) also catch and must occasionally take billfish. The number landed is unknown. But it is thought to be low particularly for white marlin (which are small and thus not impressive trophies and not particularly good to eat). Moreover, it appears that the number of billfish purposely killed is diminishing each year with the expansion of a conservation ethic throughout the recreational fishing community enforced by peer pressure at the dock and in the media. Unintentional (post-release) mortality is another matter that is, at best, not yet well-documented.

Accordingly, based on the best scientific information available, we believe that the recreational fishing sector is responsible for landing an insignificant number of Atlantic white marlin each year in comparison to the commercial sector's dead discards. There were 8+ white marlin landed by the U.S recreational sector in 2000. At a minimum, there were an estimated 3,658 white marlin discarded dead by the U.S. commercial sector as recently as 1995 (Cramer and Adams, 1999). Thus, the commercial sector is responsible for about 99.8 percent of the direct annual mortality to white marlin caused by U.S. fishers, and the (international but largely U.S.) recreational sector is responsible for landing and thus purposely killing roughly 0.2 percent. U.S. commercial vessels are estimated to have killed more than 450 times as many white marlin as did the recreational sector in the most recent year for which data are available.

As noted previously, the nation's approximately 140,000 Atlantic billfish anglers are also potentially responsible for post-release mortality of approximately 9,000 white marlin (assuming a high a post-release mortality rate of 15 percent, Hinman, 2001). The combined total mortality caused by the large recreational sector (140,000 anglers) would thus be about 9,008+ white marlin per year.

If 30 percent of the white marlin routinely caught by U.S. longline vessels are already dead and if the yearly total of such dead discards is 3,658 as estimated by NMFS (Cramer and Adams, 1999), then about 12,200 would have been released "alive." We have no estimate of post-release mortality from longlines, so we can only speculate. Considering the trauma experienced by these fish, the post-release survival rate may be quite low. The billfish may have deeply swallowed and thus have been injured severely by the offset J-hook used predominantly (probably exclusively) by longline vessels targeting swordfish. Some billfish may have spent as much as 16 hours on the line. The care given to "live releases" ranges from poor to abysmal, as noted above and in Appendix 6. Accordingly, we conservatively estimate that less than half will survive. (The actual situation could well be that few survive.) If half survived, U.S. longline vessels might be responsible for at least 6,100 additional white marlin deaths per year due to post-release mortality, or a (minimum) total mortality of about 10,000 white marlin per year. This total is 1,000 fish more than that caused by the (international) recreational sector, as estimated above. If few white marlin actually survive, the U.S. commercial sector could be responsible for a total mortality of nearly 16,000 white marlin or almost double that caused by the recreational sector. The U.S. longline fleet totals just over 200 permit holders and involves (at an average of 4 crew per vessel) 800 crew members whereas the recreational billfish sector totals roughly 140,000 anglers and crew.

Because of a very high prices paid for tuna primarily by the Japanese seafood market and for swordfish primarily by the U.S. and European markets (the major importers), all of the large pelagics have been driven to historically low population levels by decades of excessive fishing (see SCRS Executive Summaries and the Detailed Reports for each species managed by ICCAT). This has been exerted by the industrial fishing fleets of many nations using non-selective gears (e.g., longlines, entanglement or gillnets and purse seines) that efficiently catch the economically valuable target species but also kill large numbers of non-marketable species (known as bycatch). Typically, half the fish caught on U.S. longlines are discarded and 55 percent of these are already dead (Hinman, 1998). For a detailed listing of U.S. longline bycatch, see Table 5 of Draft Amendment 1 to Swordfish FMP (NMFS, 1997a). The fate of Atlantic marlin is thus tied directly to the prices paid for large tunas and swordfish. Commercial fishing that incidentally kills billfish will continue until it is no longer profitable to fish for swordfish and tunas. Bluefin tuna are by far the most valuable commercially, often drawing bids of $10 to $20 per pound dw (dressed weight or headed, tailed and gutted) to the U.S. fisherman at the dock. Bluefin are followed in commercial value by swordfish, bigeye tuna (T. obesus) and yellowfin tuna (T. albacares) at roughly $4 to $8 per pound dw, all varying with supply. Billfish bring a relatively low price of about $1 per pound dw (see NMFS, 1999a, Table 2.1.11).

A single large bluefin tuna can sell for tens of thousands of dollars. According to the Associated Press (Jan. 5, 2001), at the first auction of 2001 at Tsukiji, Tokyo's main seafood market, a single 444-pound bluefin carcass sold for an astounding price of the equivalent of $173,600 or $391 per pound. Bluefin is popularly served raw as sashimi or sushi in restaurants where a plate of slices can command a bill of more than $100. The demand for high quality bluefin created by a willingness to pay such high prices has produced a "gold rush" mentality in pelagic fisheries, worldwide. This has threatened the survival of all the large, commercially valuable pelagics (swordfish, bluefin, bigeye and yellowfin tuna) as well as the other large pelagic species, such as white and blue marlin, that are caught and die as lower value commercial bycatch on the same gear.

U.S. commercial landings of Atlantic large pelagic species totaled $56 million in 1999 (Table 5.7, NMFS, 2001a). This is composed of the following: swordfish - $19 million, bluefin tuna - $15 million, yellowfin tuna - $12 million, bigeye tuna - $5 million and sharks and their fins - $5 million.

The annual total dockside value of Atlantic marlin sold commercially by all ICCAT member nations is estimated at about $18.2 million (see Appendix 7). Together, the "flags of convenience" or rogue nations might land a smaller amount. Thus, the total commercial landings are probably less than $30 million per year.

In contrast, the international recreational fishery for Atlantic billfish (prominently including white marlin) generates much greater economic values (even at their currently low population levels) than does the commercial fishery for Atlantic billfish. The recreational fishery even generates much larger economic values than the total landed value of all Atlantic HMS species caught by the entire U.S. commercial fleet. And it does this without intentionally killing or seriously injuring the vast majority of animals caught (releases self-reported at 99 percent (Ditton, 2000)). Including tournaments and travel by anglers to popular billfish destinations, the international recreational billfish fishery in the Atlantic Ocean must be worth several billion dollars per year, as discussed below. White marlin represent a primary basis for this internationally important and extremely valuable Atlantic-wide fishery. Examples of the billfish fishery's economic values follow.

Recreational fishing is a multi-billion dollar, worldwide industry. In the United States alone, there are 230,000 billfish anglers (3.6 percent of all U.S. anglers fish for billfish), and their annual expenditures are estimated at $2.13 billion (ASA, 1996). Growth is flat in recreational fishing for demographic reasons, but saltwater fishing is in a growth mode (Ditton, 2000). Angler consumer surplus estimates for billfish vary from $550 to $1,200 per trip (SCRS/96/156[rev.]), indicating the net economic benefits from the recreational fishery are significant.

Tournament fishing has also grown dramatically. Approximately 300-400 billfish tournaments are held annually along the U.S. Atlantic coast, including the Gulf of Mexico and Caribbean (p. 2-8 of NMFS, 1999a). Prize money ranges from $50,000 to over one million dollars with bonuses of $500,000 or more for record-sized fish and large side bets by participants called Calcuttas. As an example, the winner of the Big Rock Marlin Tournament (Morehead City, NC) held in June 2001 received $942,100. For weighing-in a 515 lb. blue marlin, the crew will collect more money than the winner of the U.S. Open Golf Tournament. This tournament ended with 3 blue marlin boated (killed and weighed) and 47 billfish releases (19 blue marlin, 18 white marlin and 10 sailfish) for a 94 percent release rate (Marlin, 2001). No white marlin were killed. This is a representative tally for most "kill" billfish tournaments. Top producing tournaments in the Caribbean region include Venezuela and Puerto Rico. The March 1999 International La Guaira Billfish Shootout in Venezuela, held during the peak of their blue marlin season, set a record with a total of 256 blue marlin, 46 sailfish, 13 white marlin and four spearfish released by 118 anglers fishing on 40 boats. It broke the all-time tournament record of 190 blue marlin, set a decade ago at the Club Nautico de San Juan's International Billfish Tournament. The 2000 Shootout, held in September during the peak of their white marlin season, produced 343 white marlin releases and 16 blues.

The white marlin is the top species for billfishing from Cape Hatteras NC to the eastern tip of Georges Bank (off Cape Cod, MA) from June through October each year. It is generally the primary focus of the four large mid-Atlantic billfish tournaments: the $500,000 mid-Atlantic White Marlin Open in Cape May, NJ; the $500,000 Ocean City (MD) Billfish Tournament, the Big Rock Billfish Tournament and the Pirates Cove-Oregon Inlet Billfish Tournament, NC.

Fisher and Ditton (1992) completed an inventory of 359 billfish tournaments held in 1989 along the U.S. Atlantic coast, including the Gulf of Mexico, as well as Puerto Rico and the U.S. Virgin Islands. A total of 1,984 billfish anglers were surveyed, with 1,171 anglers responding. Respondents reported spending an average of $1,601 (excluding tournament fees) for a billfish fishing trip that lasted an average of 2.59 days, with an average of 13 trips taken each year. The average amount spent annually on billfish tournament fees was $1,856, or $546 per tournament, giving a $2,147 total expenditure per angler per trip. The total annual expenditure estimates generated from the Fisher and Ditton study indicated that in 1989, billfish tournament anglers spent an estimated $180 million in attempting to catch billfish (tournament and non-tournament trips), giving an average equivalent expenditure of $4,242 for each fish caught or $32,381 for each billfish landed (NMFS, 1999a). Ditton (1996) reported that the annual net economic benefits for the group surveyed was over $2 million. Fisher and Ditton estimated that there were 7,915 U.S. tournament billfish anglers, which translates to a $262 annual consumer’s surplus per billfish angler.

Ditton and Clark (1994) provided a description of the economics associated with recreational billfish anglers participating in at least one of 14 billfish tournaments held in Puerto Rico between August, 1991 and October, 1992. A total of 885 resident (of an estimated 1,475 resident billfish participants) and 154 non-resident anglers (82 were from the mainland United States or U.S. Virgin Islands; 72 were from other countries) were surveyed. Trip expenditures per resident averaged $711 per trip (average of 21 trips/year) and $3,945 for non-resident anglers fishing in Puerto Rico (average 7 billfish trips/year in Puerto Rico). Resident angler expenditures averaged $1,963 per billfish caught, while expenditures for non-residents averaged $2,132 per billfish caught. Ditton and Clark (1994) estimated the net economic benefits per trip at $549, yielding total annual net economic benefits of $18 million. Total resident and non-resident (U.S. citizens and foreign countries) angling expenditures were over $21 million and $4 million, respectively.

The economic activity generated by billfish tournaments alone is orders of magnitude greater than the commercial landings of Atlantic billfish by the international community. An analysis of four major U.S. billfish tournaments involving 1,000 boats was recently developed and presented to the U.S delegation at the last ICCAT meeting by IGFA Director, Steve Sloan (see Appendix 7). His analysis shows that the economic activity generated by the 1,000 participants in just four East Coast tournaments was $214.5 million. This is more than 11 times the dockside value of all marlin reported landed by all ICCAT members over the course of a full year throughout the entire North and South Atlantic Oceans ($18.2 million). There are 300-400 billfish tournaments held each year in the U.S. Atlantic Coast and the Caribbean (NMFS, 1999a).

Big game fishing also generates substantial economic activity and employment for local economies. For example, the regional economic impact generated annually by several billfish fisheries is estimated as follows: Manzanillo, Mexico - $9.1 million (Chavez, 2000); Costa Rica - $28 million (Ditton and Grimes, 1996), Puerto Rico - $38 million (Ditton and Clark, 1994); and the Baja, Mexico - $70 million (Ditton, et al. 1996). These values are separate from economic activity associated with airline travel, which is also substantial but accrues elsewhere. Since sport fishing for billfish is almost entirely a catch-and-release fishery, these economic benefits flow in perpetuity, if the populations are maintained at a healthy level.

The Caribbean in general, and several sites in particular, such as the Virgin Islands, Puerto Rico and Venezuela, are known worldwide as "billfish capital of the world." The true value of this regional asset is inestimable, especially so in light of the fact that the billfish community now voluntarily releases nearly all (self-reported at 99%, according to R. Ditton, 2000) the billfish they catch thus perpetuating the basis for the fishery indefinitely. However, the tourism, jobs and economic benefits depend entirely on the existence of billfish concentrations. Anglers will travel long distances, often with their own boats and crews, but only to destinations where billfish or other big gamefish catch rates are high. However, as will be shown later, commercial overfishing (primarily longlines) targeting the more valuable (and numerous) swordfish and tunas is driving Atlantic-wide white marlin populations (and to a slightly lesser degree, blue marlin) rapidly toward extinction.